By Janice Lobo Sapigao

“Every woman has a grave deep inside her.” – Michelle ‘Mush’ Lee

When we buried my father, my mother buried her feelings for him. When she did, we all did. To this day, she hides telling my brother, William, and me of the history of her love with and for him. I can tell. She smiles in response when I ask her questions about my father’s personality. She leaves our conversations for the bathroom when I wonder out loud about her life in the Philippines. She grunts when I tell her to tell me something, anything. She laughed and petted me when I told her, at age twenty-five, that I was learning Ilokano so that I could understand her better. My mother seals my father from us, especially from me – her daughter, the inquirer, the writer, the one who makes her speech tiptoe – as though her secrets and our questions keep him at bay. This secrecy might be for her what keeps him alive. For me, it’s why I write, ask questions, read, and research.

I feel for this woman, my mother.

I think their love was forbidden. But it’s not the kind of forbidden that stays in one place, no, it’s the kind that multiplies and moves on. I think I’m not supposed to know, much less write about, how our family – her parents and siblings who are my grandparents and uncles and aunties – did not approve of their courtship for reasons I can only imagine from their collective silence. I think they met in the Philippines before she immigrated to the United States in 1978. I think he served in Saudi Arabia for the U.S. Army during the time of their courtship. I think that I cannot simply ask my mother about my father without watershed and flood and drowning; that I am actually asking her to fasten a nail to the wall of a dam that holds him behind it, that constructs her safety. I think that I am asking about shame. I think my asking her to open up is a breach, is asking her to re-live what we both grieve but cannot yet accept. And because I empathize, because I know that my questions require her, this woman, my mother, to undo a silence that’s kept us afloat, then I think this is how shame multiplies. How can I ask my mother to unravel this silence? What are we both afraid of? When will we heal?

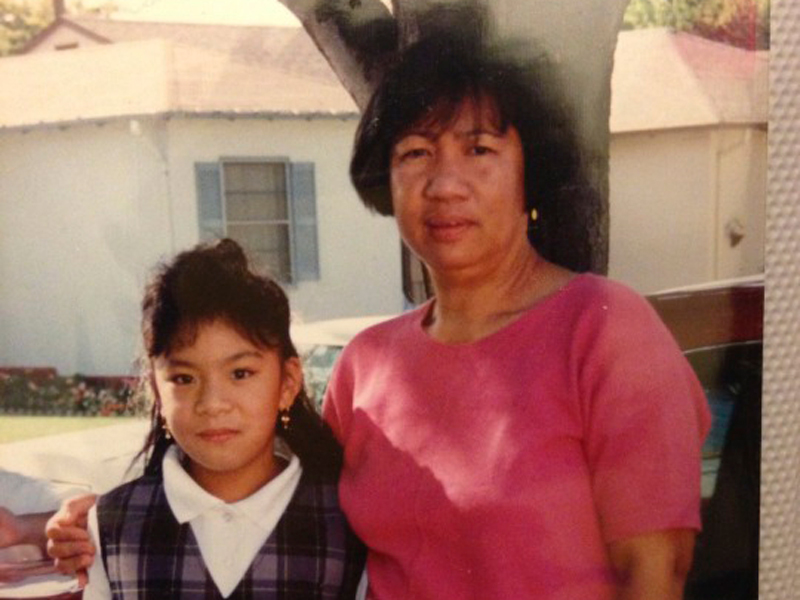

I write extensively, privately, publicly on what happened when my father passed away twenty years ago. I was six years old. This meant that I was so young that I didn’t know what was going on. Could you imagine a little girl smiling at her father’s funeral? My second book, Like a Solid to a Shadow, was incited by the memory of taking this photo. There are pictures as proof in my family photo albums from that year. My brother remembers running away from the burial site as he saw our father being lowered into the ground, our oldest cousin chasing after him. I remember my mother’s guttural bawls, calling back for my father in Ilokano. I remember remaining silent, everyone looking at me, their eyes just above the ground where I stood because I thought that was what I was supposed to do for my family at that time. Can you imagine a little girl not saying anything at her father’s funeral? Now, I cry, remember, bury and uncover my feelings when his death anniversary comes. My father dies every time I tell someone new that I am fatherless this way. He lives every time I think about him. I write to respectfully remember, but also to resurrect his stories.

“Have you ever heard a butterfly scream?” – youth poet

When she pretended to choke herself with her necklace in French class, I knew something was wrong. My best friend in middle school, Gladys, sat next to me, pinching and pulling the back of her necklace to press its front against her throat. “Hey dude,” I think she called to me, “what would you do if I killed myself?” Keeping my eyes on the instructor, I whispered, “What’s wrong?” I was familiar with these thoughts. She replied, “I don’t know. Just wondering.” I couldn’t bear to look at her because her words mirrored my own insidious ones that arose years before I had ever met her.

Our close girlfriend of our trifecta, Patricia, also contemplated self-injury. Patricia’s family troubles continued with us through high school right into when I left San Jose, CA for college in La Jolla, CA and up until our friendship ended when I graduated. In fact, it wasn’t until I was a student at UC San Diego where I majored in Ethnic Studies and minored in Urban Studies & Planning that I acquired a language for the injustices I’d seen and the ineffability I’d felt as a young Pinay. I was acquiring a language for my rage. I actively sought out Asian American History classes and seminars, worked with professors and made appointments with counselors and staff in order to seek answers to questions that had erupted from me. I began my own research projects with Ethnic Studies Professor Yen Le Espiritu as my advisor. I thought the affect of my heart needed to match the rigor of my intellectual work. These questions, “Why don’t I know myself? Who am I? Why can’t I talk about the things that have been on my mind for years?” had always been inside me.

We Pinays, we were screaming butterflies. It wasn’t until college that I learned that Pinay contemplation and Pinay suicide rates were a public health issue of my generation. In so many phone conversations, text conversations, and women’s healing circles, and within myself, there was always an understood and accepted silence where we worked through our problems, our traumas and histories in a private space. We worked and thought together, alone and in our writings. I worked in a way that Patricia did not, could not. While I was at school five hundred miles away from home and from the roots of some of my familial problems, Patricia, and even Gladys, were around the city of theirs all the time.

In many ways, I still feel a little girl inside me asking questions, seeking answers, hating being shushed, working towards understanding and critically remembering and writing in her diary. My little girl, she is safe with me. She is my anthology, my empowered sense of self, my father’s daughter, my mother’s interpreter, and a source of friendship. In many ways, I still feel a little girl inside me asking questions, seeking answers, hating being shushed, working towards understanding and critically remembering and writing in her diary. My little girl, she is safe with me. She is my anthology, my empowered sense of self, my father’s daughter, my mother’s interpreter, and a source of friendship.

About the Author:

Janice Lobo Sapigao is a Pinay poet, writer, and educator from San José, CA. She is the author of two books of poetry: microchips for millions (Philippine American Writers and Artists, Inc., 2016) and Like a Solid to a Shadow (Timeless, Infinite Light, 2017). She is also the author of two chapbooks: you don’t know what you don’t know (Mondo Bummer Books, 2017) and toxic city (tinder tender press, 2015). She is a VONA/Voices Fellow and was awarded a Manuel G. Flores Prize, PAWA Scholarship to the Kundiman Poetry Retreat. She is the Associate Editor of TAYO Literary Magazine. She co-founded Sunday Jump. Her work is also published in online publications such as The Offing, NBC Asian America, KQED Arts, CCM-Entropy, the Asian American Writers’ Workshop’s The Margins, and AngryAsianMan.com, among others. She is the Associate Editor of TAYO Literary Magazine. She teaches English at San José City College.